Developing solutions to the lifestyle-related threat to U.S. national security

By Jean Tips

ACLM Senior Director of Communications & Public Affairs

October 9, 2023

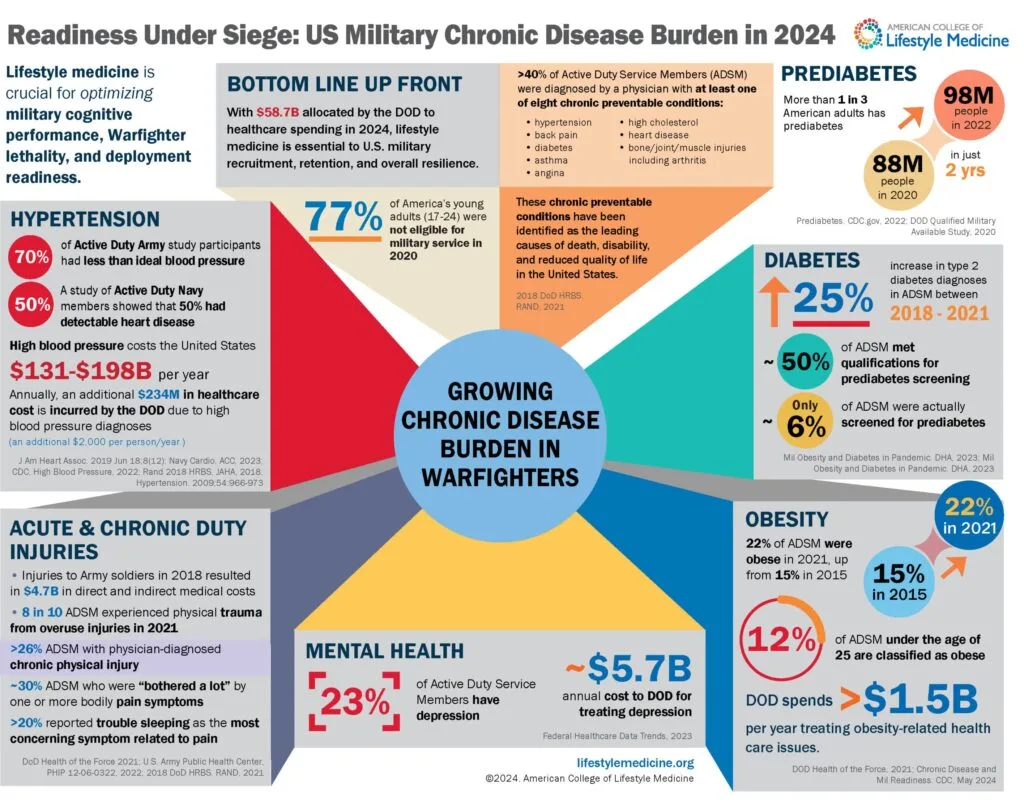

The same lifestyle-related health issues that have had a long-standing impact on disease and death in the U.S. are now recognized as an immediate threat to national security. This threat spans throughout every stage of the military lifecycle, significantly impacting recruitment, retention, and readiness across all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces; veteran populations are also disproportionately burdened by these lifestyle-related health concerns . Recent military media reports have highlighted this problem, but missing from media coverage thus far have been the collaborations across government, NGOs, industry, and academia, providing evidence-based solutions for the problem.

The need for sustainable health solutions is clear

Recent studies show the vast majority of age-eligible Americans are unfit for military service. A 2022 Pentagon study shows that 77% of young Americans would not qualify for military service without a waiver due to being overweight, having mental or physical health problems, or a history of prior drug use. This is an increase from the Pentagon’s 2020 Qualified Military Available Study that shows a 6% increase from the 2017 Department of Defense research that showed 71% of Americans would be ineligible for service.

Another recent study showed that recruits from Southern States, which have higher prevalence of chronic disease, are generating a disproportionately higher health care cost burden that is linked to significantly higher rates of musculoskeletal injures (MSKIs) sustained during basic training. MSKIs are considered the greatest medical impediment to military readiness, are highly correlated with physical fitness, and cost the U.S. Department of Defense an estimated $3.7 billion annually across all service branches. In this most recent study, Army recruits from a cluster of Southern states accounted for nearly 50% of total national costs related to MSKIs amongst all Army recruits nationally.

In addition, another recent study showed that between 2018 and 2021, the prevalence of obesity, prediabetes, and diabetes increased among active service members. The largest relative increases in obesity prevalence were in the youngest (<30 years) age categories. This is of significant concern as service members with elevated BMI and other metabolic disorders may not meet requirements for theater deployment.

Lifestyle medicine practice is growing within the military

However, efforts are underway to solve this alarming issue. The breadth of lifestyle medicine practice is growing within the military as a whole. Already, there are multiple clinics implementing Lifestyle & Performance Medicine approaches to optimize warfighter health in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy, as well as the National Guard and Reserve. These clinics deliver the same foundational six tenets of lifestyle medicine with an added focus on human performance and typically integrate care deliver through a range of various health care providers across many specialties. There are also eight military graduate medical education programs that have adopted the lifestyle medicine residency curriculum.

Partnerships are key to making further headway

Some examples:

- The Air Force Lifestyle & Performance Medicine Working Group has formally adopted the field and practice of lifestyle medicine into what is rapidly gaining traction in the Department of Defense as Lifestyle & Performance Medicine. Focusing on not only preventing, treating, and reversing disease, but also leveraging human performance optimization, this approach to health maintenance is a modality to achieve preserved deployment readiness and sustain general health for service members. The foundations of this approach were developed in partnership with the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM). A recent news article highlights this work.

- The Physical Activity Alliance (PAA) is one of the nation’s broadest coalitions dedicated to promoting physical activity, with representation from government, industry, NGOs and academia. In an effort to address the national security crisis posed by a physically underactive population, the PAA recently supported the addition of a Military Settings Sector to one of its cornerstone initiatives, the National Physical Activity Plan (NPAP). The NPAP is a comprehensive set of policies, programs, and initiatives designed to increase physical activity in all segments of the U.S. population, in order to increase the health, safety, and security of the nation.

- The National Guard and the Uniformed Services University’s Consortium for Health and Military Performance (CHAMP) have collaborated in developing and delivering curriculum to Guard members to become “human performance optimization integrators.” These integrators return to their formations as embedded assets helping their fellow service members improve all aspects of their fitness, health, and readiness.

- The Citadel, American Heart Association and the University of South Carolina partnered with the U.S. Army Public Health Center to conduct the research cited above that highlights the MSKI problem and associated costs.

- Another research collaboration between CDC, private industry, and the Uniformed Services University resulted in this study published in the Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Initial progress at the policy level

Efforts are also underway at the policy level. For example, IHRSA, the Global Health and Fitness Association, is urging that the FY 2024 National Defense Reauthorization Act include provisions for improved exercise programming and access for active-duty military personnel and families as well as pre-basic training recruits.

Former US Air Force Flight Surgeon Regan Stiegmann DO, MPH, FACLM, who has actively participated in integration of lifestyle medicine into the military, is optimistic about the potential it has for addressing the health issues impacting national security. “Implementing lifestyle medicine (and Lifestyle & Performance Medicine) are the most robust and evidence-based approaches to effectively and sustainably achieve the Military Health System and Defense Health Agency’s quadruple aim of improving readiness, improving health, improving care and decreasing cost,” Dr. Stiegmann said.