Reframing sleep: insomnia-centric advice for better rest

Part one of this two-part series discussed how insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea are both significantly more prevalent than insufficient sleep opportunity/prioritization, and therefore, our general sleep advice should cater to people with these diagnoses. This post will focus on insomnia and introduce a revised approach to general sleep health advice that prioritizes an insomnia-informed perspective.

By Michelle Jonelis, MD, DipABLM, DBSM

Founder and Chief Medical Officer of Lifestyle Sleep Clinic

May 29, 2025

A physiological process, not an achievement

As we discussed in part one, sleep is not a voluntary behavior but rather a physiological process influenced by a complex interplay of factors: light exposure, physical activity, social rhythms, stress levels, and genetics. Sleep is a byproduct of these factors, not something we can directly control. This fundamental concept should shape our messaging around sleep health.

Stop emphasizing the importance of ‘good sleep’

Public health messaging frequently highlights that “good sleep is essential for health.” However, this wording implies that good sleep is something one can actively achieve. Instead, we should say: “Setting up the conditions for restorative sleep is essential for health.” This reframe shifts the focus to what individuals can control: the conditions that facilitate quality sleep.

Normalize night wakefulness and focus on rest

Wakefulness during sleep is normal and healthy. Even if someone feels they “slept through the night,” polysomnography shows that 10–20% of sleep time is spent awake. From an evolutionary perspective, periodic wakefulness makes sense: it allows us to monitor our environment and respond to needs like a full bladder and adjusting our body position. When nothing demands our attention, these brief wake-ups often go unnoticed.

It is also normal to take up to 30 minutes to fall asleep and to wake up one to three times per night for a total of at least 30 minutes.¹ It is normal for there to be a transition state between wakefulness and sleep, and there is evidence to show that this quiet wakefulness is actually beneficial for brain health.²,³ However, many individuals misinterpret these normal experiences as signs of poor sleep quality.

Instead of framing nighttime as only for sleep, we should normalize it as a time for both rest and sleep. Because many people have assumed that waking up during the night is abnormal, they haven’t learned how to handle these moments in a restful way. As a result, they often turn to their phones for distraction. Educating patients about the benefits of quiet wakefulness, such as mind wandering, and offering strategies like deep breathing, mindfulness exercises, and visualizations can help them navigate nighttime wakefulness more calmly and effectively. If they are unable to remain calm in bed, they can get up temporarily and engage in a screen-free distracting activity such as reading or listening to audio content, then return to the bed once they are calm again.

Strengthen circadian rhythms and promote healthy lifestyle behaviors

Rather than fixating on sleep duration, we should help patients establish strong circadian rhythms and promote a lifestyle conducive to quality sleep. This includes maintaining a consistent wake time, prioritizing spending time outdoors and in bright light throughout the day, and optimizing the other five lifestyle medicine pillars.

Research is increasingly showing that sleep regularity is more closely associated with health outcomes than sleep duration.⁴ A stable wake-up time (no more than one hour variability throughout the week) seems more important than a stable bedtime because it is the wake-up time that sets our clock for the day and anchors our circadian rhythms. Bedtimes must be a bit more flexible to accommodate normal variability in sleep duration. Rigidly enforcing both a fixed bedtime and wake-up time can lead to more nighttime wakefulness and more sleep anxiety rather than better sleep.

Most people don’t realize that getting sufficient sunlight exposure during the day improves our sleep quality much more than avoiding blue light before bed. Research actually suggests that the more time one spends outdoors, the healthier their sleep and overall metabolism without a clear ceiling effect.⁵

Optimizing the other five lifestyle medicine pillars by eating copious plants, obtaining both cardiovascular exercise and resistance training, connecting with others, managing stress and reducing use of risky substances is another essential part of promoting healthy sleep. In particular, consuming alcohol seems to be especially disruptive to sleep quality and minimizing alcohol intake should be an essential part of any sleep guidelines.

Understand how insomnia develops: the sleep-stress response

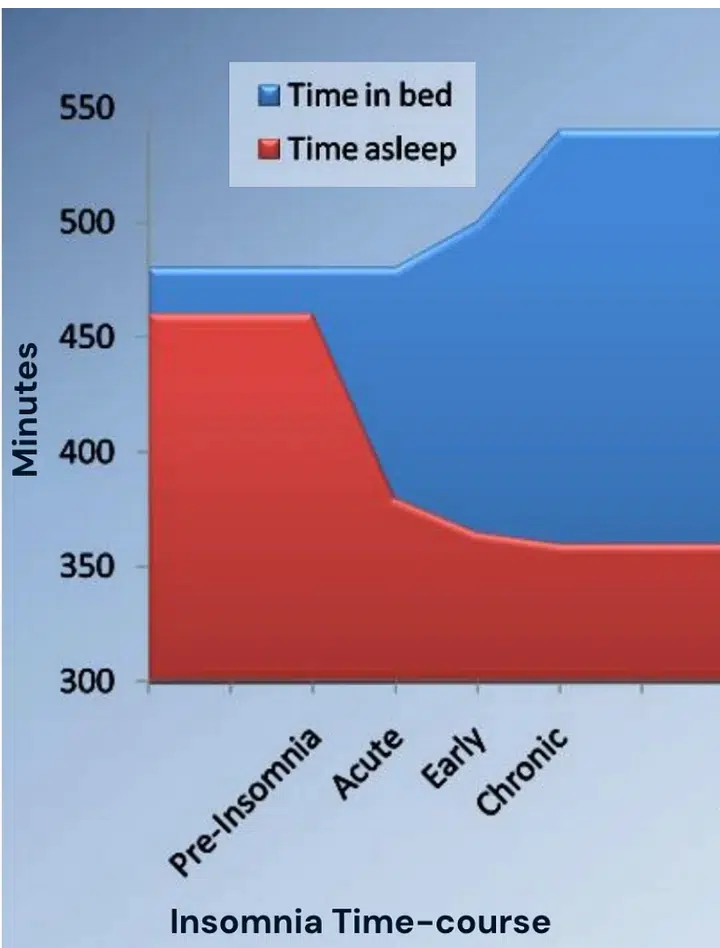

Insomnia typically develops when the sleep-stress response (commonly referred to in the insomnia world as “hyperarousal”) has been activated. Before developing insomnia, most people experience occasional nighttime wakefulness but don’t dwell on it. Their sleep efficiency, the percentage of time spent asleep while in bed, typically falls between 80–90%. However, when something triggers the sleep-stress response, sleep patterns begin to shift.

Figure 1. The Sleep-Stress Response and Compensatory Expansion of Time in Bed. (Adapted from Perlis, M., Posner, D., & Ellis, J. (2015). Advanced Practice of CBT‐I [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/)

Figure 1. The Sleep-Stress Response and Compensatory Expansion of Time in Bed. (Adapted from Perlis, M., Posner, D., & Ellis, J. (2015). Advanced Practice of CBT‐I [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/)

The sleep-stress response is a natural reaction to stress, designed to keep us alert to potential dangers. In times of worry, whether about finances, health, family, work, or major world events, the brain instinctively lightens sleep, increases awakenings, and reduces total sleep time. This response evolved as a survival mechanism: if a predator attacked the village or a wildfire threatened, sleeping too deeply could be dangerous. Other triggers, such as illness, grief, or even excitement, can also activate this response.

During these stressful periods, we often experience heightened environmental awareness, sometimes drifting in and out of wakefulness or remaining semi-aware of our surroundings while still receiving many of sleep’s restorative benefits. The underlying mechanism is increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which primes the body for action. As a result, sleep durations can temporarily fall well below seven hours without necessarily being harmful in the short term. During the day, we may have the sensation of feeling tired but wired: mentally drained from processing stress yet still physiologically alert.

The problem is that most people aren’t taught about the sleep-stress response. Instead, they’re led to believe that uninterrupted, seven-to-eight-hour sleep is essential every night. When their sleep becomes fragmented, they panic, assuming something is wrong. They mistakenly attribute their daytime fatigue to poor sleep, rather than recognizing that both lighter sleep and tiredness are natural responses to stress.

A common but misguided reaction is to extend time in bed to “catch-up” on lost sleep. (See figure 1 above). However, this backfires because the issue isn’t insufficient time in bed, it’s increased sympathetic nervous system activation. Spending more time in bed only further increases nighttime wakefulness and weakens the circadian rhythm, and the individual becomes increasingly stressed about their sleep. Research shows that individuals can remain in this state of chronic hyperarousal and a maladaptive sleep schedule for many years, leading to chronic insomnia.

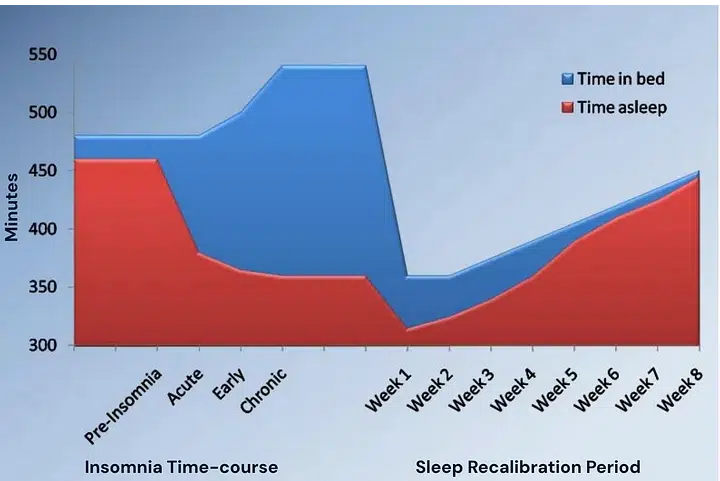

Sleep recalibration and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

Recognizing the sleep-stress response, researchers in the 1980s developed an effective intervention: sleep recalibration. Initially termed “sleep restriction therapy,” this strategy involves reducing time in bed to align with actual sleep needs, thereby consolidating sleep. When combined with cognitive interventions, this forms the foundation of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), the gold standard insomnia treatment. Studies show that CBT-I improves sleep in 75-80% of insomnia patients and provides long-term benefits superior to sedative medications.

Figure 2. Addressing the Sleep-Stress Response with Sleep Recalibration. (Adapted from Perlis, M., Posner, D., & Ellis, J. (2015). Advanced Practice of CBT‐I [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/)

Figure 2. Addressing the Sleep-Stress Response with Sleep Recalibration. (Adapted from Perlis, M., Posner, D., & Ellis, J. (2015). Advanced Practice of CBT‐I [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/)

CBT-I has been shown to be effective in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, depression, anxiety, PTSD, chronic pain, perimenopausal symptoms, and other health issues that might be contributing to poor sleep. CBT-I is classically performed one-on-one or in a group setting with a trained psychologist. But today there are a number of high-quality app- and web-based options as well as self-help books. As our brain feels less stressed over time and our system recalibrates, research shows that sleep will naturally lengthen and deepen again.

Why sedatives fail

Prescription and over-the-counter sedatives do not address the underlying sleep-stress response. While they may temporarily increase sleep duration or reduce awareness of wakefulness, tolerance develops over time, leading to recurrent insomnia. By masking the problem rather than resolving it, sedatives prevent individuals from adopting effective strategies such as sleep recalibration and stress management techniques.

Preventing insomnia through improved sleep health messaging

To reduce the burden of insomnia, public health messaging should emphasize the following ten strategies:

1. Educate Patients on the Sleep-Stress Response

Stress can lead to lighter sleep, more awakenings, and shorter durations. This is a normal physiological response.

2. Normalize Night Wakefulness

Awakening during sleep is natural. Patients should be reassured and taught relaxing activities to engage in when wakefulness occurs. Electronic screens are not appropriate for coping with night wakefulness and should be kept out of reach of the bed.

3. Teach Sleep Recovery Strategies

When sleep is disrupted by stress, individuals should:

- Limit time in bed to more closely match actual sleep need (reducing sleep opportunity to six to seven hours for one to two weeks is typically effective).

- Engage in “constructive worry” by setting aside time each evening to write down thoughts and concerns.

- Increase activities that reduce stress, such as exercise, time in nature, and positive social interactions.

4. Promote Long-Term Stress Management

Consider evidence-based psychotherapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and mindfulness training to help manage chronic stress and anxiety.

5. Encourage Consistent Wake Times Over Fixed Bedtimes

A stable wake-up time (within an hour of consistency) is more beneficial than rigidly enforcing a fixed bedtime.

6. Define Appropriate Sleep Opportunity, Not Sleep Duration

Choose an appropriate sleep opportunity window (the time from when you close your eyes to sleep until when you get out of bed for the day) for your age and genetics. Most people do best allowing for a sleep opportunity of seven to nine hours with a wake-up time around sunrise but there is significant population variability. If wakefulness exceeds 30 minutes during the night, sleep opportunity should be reduced.

7. Normalize Variability in Sleep Patterns

Sleep needs fluctuate due to stress, exercise, hormonal changes, cognitive load and many other external factors. Some nights you will sleep more deeply, and other nights less. If you are not feeling sleepy, it’s okay to stay up until sleepiness sets in, but still wake up at your usual time.

8. Optimize Circadian Rhythms

- Get outside for at least 60 minutes daily, including 10 minutes before work or school.

- Keep indoor lighting as bright as possible and window shades fully open during the day.

- Keep the lights dim/warm-tinted for 1-2 hours before bed. If an individual is dozing before bedtime, reduce this interval to 30 minutes before bedtime.

9. Highlight the Role of Lifestyle Factors

A plant-predominant eating pattern, regular physical activity, stress management, strong social connections and avoiding alcohol and addictive substances all contribute to better sleep quality.

10. Use CBT-I Instead of Sedatives

When chronic insomnia develops, patients should be referred for CBT-I rather than relying on sedatives. If they are already taking sedatives, the dosage should be stabilized, then eventually weaned during CBT-I. Find a local CBT-I provider here: https://www.behavioralsleep.org/index.php/united-states-sbsm-members.

Final thoughts

Current sleep health messaging has unintentionally fueled sleep anxiety and contributed to the insomnia epidemic. By shifting our approach to emphasize circadian health, stress management, and behavioral strategies, we can help patients develop a healthier, more sustainable relationship with sleep.

Instead of striving for perfect sleep, patients should focus on setting the conditions for restorative sleep, embracing rest, and maintaining strong daily rhythms. These principles, informed by the science of insomnia, should form the foundation of lifestyle medicine’s approach to sleep health.