The sleep pillar: Is our messaging helping or hurting?

Public health messaging implies that Americans are experiencing an epidemic of sleep deprivation. Is it possible this narrative has caused an even bigger problem of sleep anxiety?

By Michelle Jonelis, MD, DipABLM, DBSM

Founder and Chief Medical Officer of Lifestyle Sleep Clinic

May 22, 2025

As lifestyle medicine clinicians, we know that sleep is critical to health. But what if the way we talk about sleep is unintentionally worsening our patients’ struggles? Too often, well-meaning advice about sleep fails to help—and may even hurt—the patients who need our guidance the most. It’s time to reframe our approach.

The three most common sleep issues we see

In lifestyle medicine, the three primary sleep issues we encounter are: 1) Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), 2) insomnia 3) insufficient sleep opportunity/prioritization.

The majority of media and public health messaging has focused on issue #3: an assumption that we are experiencing an epidemic of sleep deprivation due to Americans simply not prioritizing sleep. The message is clear—sleep is essential, and short-changing it harms health. Yet, a large body of research shows that the prevalence of adults reporting less than seven hours of sleep per night has remained relatively stable for decades, hovering around one-third of adults.¹ It’s actually not even clear that modern humans actually do sleep less than our ancestors, and several large meta-analyses have concluded that the claims regarding an epidemic of sleep deprivation in the western world are largely unfounded.²

What has changed, however, isn’t how much sleep we get—it’s how bad we feel about our sleep.

Figure 1. The 3 most prevalent sleep problems facing the US today.

Figure 1. The 3 most prevalent sleep problems facing the US today.

The rising tide of insomnia

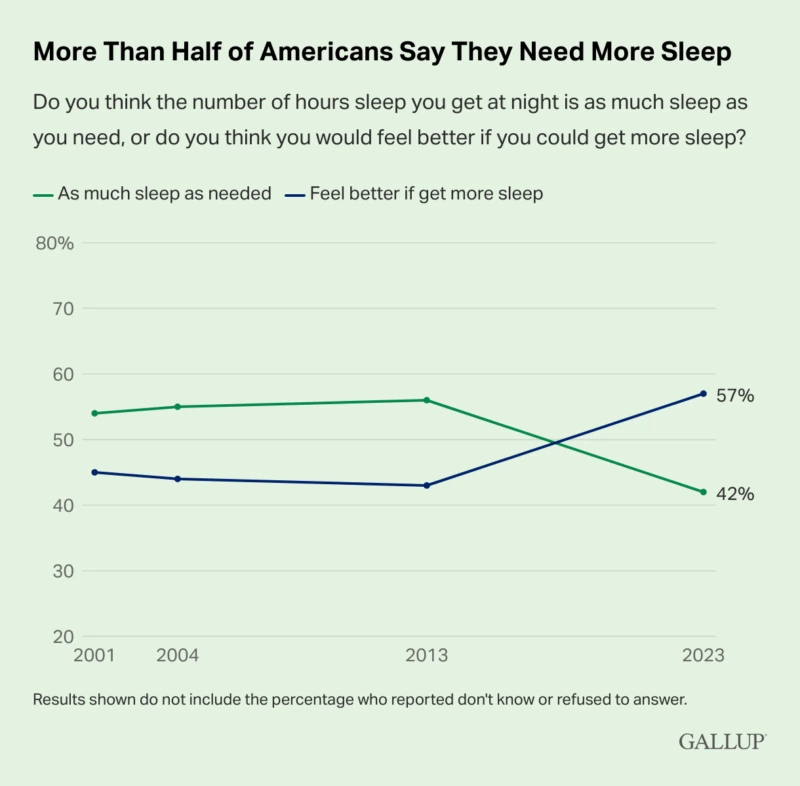

Insomnia, defined by many as difficulty sleeping despite sufficient opportunity, IS increasing in prevalence—particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2023 survey by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine found that over 50% of Americans often or always struggle with sleep onset or maintenance and only 8% report never experiencing these disruptions.³ A separate 2023 Gallup poll found that 57% of Americans say they “need more sleep,” up from 43% in 2013.⁴ It’s no surprise, then, that 75% of Americans now use prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal sleep aids occasionally or regularly.⁵ We think our sleep is somehow lacking and are desperate to fix it.

This all means the bigger sleep problem in our exam rooms isn’t sleep deprivation due to inadequate prioritization of sleep. It’s insomnia—patients struggling to sleep despite carving out more than enough time in bed.

Ironically, public health campaigns emphasizing sleep’s importance are likely a major contributor to this increase in insomnia. Sleep has become a multi-billion-dollar industry and a national obsession, leading to increased sleep effort—people trying harder to sleep and failing.⁶

Figure 2. Gallup poll results showing a recent increase in Americans who say they need more sleep contrasted with the age-adjusted prevalence of adults who report sleeping fewer than 7 hours per night.⁷

Figure 2. Gallup poll results showing a recent increase in Americans who say they need more sleep contrasted with the age-adjusted prevalence of adults who report sleeping fewer than 7 hours per night.⁷

The illusion of control

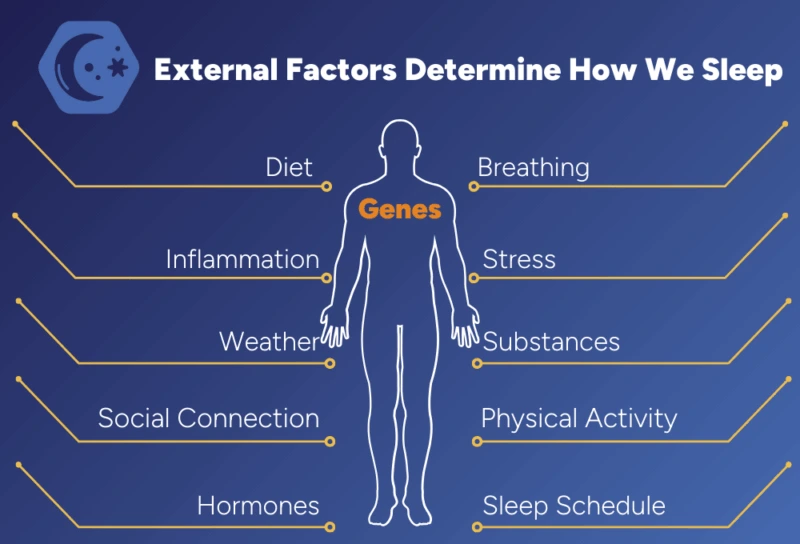

Unfortunately, unlike diet or exercise, sleep is not a voluntary behavior. It is a physiological process that emerges from a complex interplay of factors—light exposure, physical activity, social rhythms, stress levels, and even genetics. Telling patients they must “get at least seven hours” assumes that sleep is something they can directly command, when in reality, they can’t.

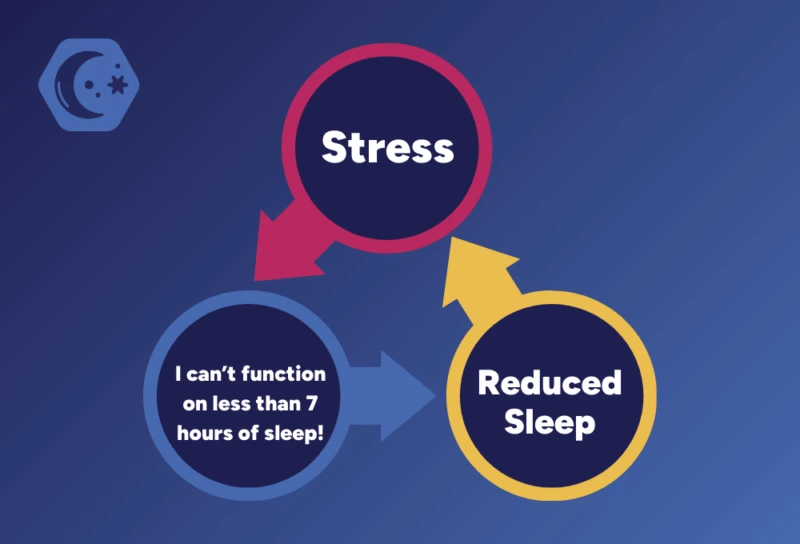

Patients internalize this messaging, leading to sleep anxiety and a counterproductive focus on achieving perfect sleep. They lie awake, staring at the clock, worrying that they are failing at a fundamental aspect of health—all of which makes sleep even more elusive.

Figure 3. The insomnia cycle.

Figure 3. The insomnia cycle.

Consumer wearable data is challenging our assumptions

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that adults get a minimum of seven hours of sleep per night⁸, but real-world data from wearables suggests that this advice is flawed. Population studies using consumer wearable data or research grade actigraphy have consistently significantly shown lower sleep durations for adults than what was previously reported in the literature, which relied on self-report.⁹ Similarly, population-based studies correlating adverse health outcomes and mortality with sleep duration have found the best health outcomes for seven to eight hours of sleep per night when relying on self-reporting but typically fail to find any adverse health outcomes for sleep durations >6 hours when using more objective, wearable data.¹⁰ Unlike self-reported sleep duration, which, on average, stays constant throughout adulthood, wearable-measured average sleep duration shows a decline with age.¹¹ This new data strongly suggests that six to seven hours of wearable-measured sleep duration per night may be perfectly normal and healthy for a substantial portion of adults.

Obstructive sleep apnea is also much more prevalent than neglecting sleep

Meanwhile, OSA still remains underdiagnosed. Population studies have put the prevalence of mild OSA (AHI 5–15) at 50% to >80% and moderate to severe OSA (AHI>15) at 20% to 50%, depending on the testing and scoring methods used.¹² ¹³ Given these staggering numbers, more public health messaging should be focused on OSA.

When neglecting sleep is the real problem

While much sleep messaging creates unnecessary anxiety, some patients truly don’t allow enough time for sleep. Shift workers, caregivers, those juggling multiple jobs, middle and high school students with early school start times and individuals who deprioritize sleep for work or entertainment still need support in creating more opportunities for sleep. Rather than fixating on an exact number of hours, we can help these patients identify barriers, make practical adjustments, and reframe sleep as essential recovery—ensuring they have the chance to get the rest they need.

Choosing our words carefully

It’s time to shift our sleep discussions away from rigid sleep goals and toward reducing sleep-related distress.

- Instead of “You need at least seven hours,” try “Your body will get the sleep it needs.” Sleep duration is not something we can force, and focusing too much on it can create anxiety.

- Instead of “Better sleep hygiene will fix your sleep,” remind them “Good habits help set the stage, but sleep itself cannot be controlled.” Overemphasis on sleep hygiene can lead to compulsive behaviors and frustration when these efforts don’t work.

- Instead of “If you don’t get enough sleep, your health will suffer,” try “Sleep is a natural outcome of many interconnected factors—let’s explore which ones in your life might need adjustment.” Rather than framing sleep as something to achieve, this approach emphasizes optimizing the conditions that allow sleep to emerge naturally.

Figure 4. A picture I created for my patients to help them understand some of the aspects that determine how they sleep at night.

Figure 4. A picture I created for my patients to help them understand some of the aspects that determine how they sleep at night.

Shifting the national conversation

It’s time to update our sleep messaging. Sleep isn’t something we achieve through effort—it’s something that happens when the conditions are right. As lifestyle medicine clinicians, we are uniquely positioned to help patients create those conditions.

The new mantra we should promote is: “Sleep isn’t something you achieve; it’s something that unfolds when the right conditions are in place. Focus on removing barriers, and better sleep will follow.”

Let’s move beyond outdated sleep duration recommendations and generic sleep hygiene advice and guide our patients to understand the real roots of their sleep struggles—so we can truly support them in optimizing this essential pillar of health.

Coming Up

Please stay tuned for our next ACLM blog post on sleep which will outline what Insomnia-Centric Sleep Health Advice might actually look like.